Experts say illegal immigration has not increased crime in the United States. But some politicians and law enforcement officials continue to insist otherwise.

The first casualty in the war of words over illegal immigration seems to have been the facts.

Political rhetoric about a wave of crime engulfing the nation from our southern border is flat wrong, according to widely trusted and long-used crime reporting data. Crime is down in the United States — nationwide and along the border.

And, in a deeply ironic twist new research shows that immigrants of all kinds might actually make communities safer.

All the while, Latino immigrants who are coming, or have already settled, in the United States continue to be labeled a serious threat to the country.

The Numbers

The most recent estimate from the U.S. Department of Homeland Security’s Office of Immigration Statistics is that 10.8 million unauthorized immigrants live in the United States. This number of illegal immigrants trended upward from the 1990s to early 2000s and dropped off around 2004, according to the Pew Hispanic Center, a non-partisan research organization. (Experts have debated the cause of the mid-2000s decline, arguing whether increased border enforcement or economic trends — or other factors — made the difference.)

Immigration & Crime

- Main

- Immigration Rose, Crime Dipped

- The Numbers

- Arizona’s Story

- A Latino Paradox

- Moral Panic

Explore this topic:

As illegal immigration to the United States has declined in the past few years, violence has raged in Mexico, due to ongoing wars among drug cartels and between cartels and the government. Some of that violence has come close to the border and has sometimes spilled over it.

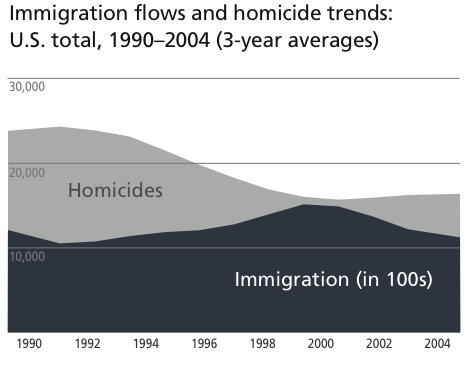

But during the big growth period for illegal immigration, the early 1990s to early 2000s, the national crime rate dropped, year after year, according to the FBI’s Uniform Crime Reporting Program. The FBI data shows that crime decreased every year from 1992 to 2004. During this period illegal immigration peaked, according to the Pew Hispanic Center.

“Rather than undergoing a continuous increase in immigrant levels as is commonly perceived, the United States experienced a sharp spike in immigration flows over the past decade that had a distinct beginning, middle and end,” wrote Pew researchers Jeffrey S. Passel and Roberto Suro in their 2005 report. “From the early 1990s through the middle of the decade, slightly more than 1.1 million migrants came to the United States every year on average. In the peak years of 1999 and 2000, the annual inflow was about 35 percent higher, topping 1.5 million. By 2002 and 2003, the number coming to the country was back around the 1.1 million mark.”

So crime rates declined during the period when immigration increased. The FBI’s UCR data also shows that crime rates inched up slightly in 2005 and 2006 — during a period when illegal immigration was on the decline, according to Pew.

By the time Arizona’s legislators first began debating the state’s controversial immigration enforcement law, SB 1070, and other “get tough” laws pertaining to immigration, crime AND immigration were on the decline nationally. From 2007 to 2009, the national crime rate declined, as did illegal immigration.

The initial estimates, released in December 2009 from the Preliminary Semiannual Uniform Crime Report’s violent crime statistics for 2009, show national crime rates continuing to decline. Compared to 2008, violent crime is down 4.4 percent with property crime down 6.1 percent. And the border region has enjoyed that decline in crime along with the rest of the country, a fact President Barack Obama pointed out in his July 2010 speech on immigration.

Arizona’s Story

The creators of Arizona’s tough new immigration law, SB 1070, which brought national attention to the state, originally dubbed the measure the “Support Our Law Enforcement and Safe Neighborhoods Act” and argued that the law is a serious crime-fighting policy.

[Parts of SB 1070 have been put on hold by a federal judge.]

Jan Brewer, Arizona’s governor and a supporter of SB 1070, has inaccurately claimed that most illegal immigrants have prior criminal records and connections to the cross-border drug trade. These assertions have been flatly refuted by law enforcement officials.

Immigrants who cross the border illegally or who stay in the country illegally are definitely breaking federal law. But Border Patrol officials estimate that 80 percent of those the agency detains in their busiest sector — in southern Arizona — have no other criminal record.

And despite the pictures of fence-jumpers regularly shown on television news, a large portion of illegal immigrants initially came into the United States legally. An estimated 40 percent are visa “overstayers,” who were welcomed into the country by the U.S. State Department and walked, drove or flew over the border legally, according to Bernard Schwartz, a research fellow at the Council on Foreign Relations, a non-partisan research organization. In March 2010 Schwartz told the U.S. House Committee on Homeland Security that multiple groups, including the Immigration and Naturalization Service (before it was re-organized and its name was changed) and the Pew Hispanic Center, had settled on a number around 40 percent. But Schwartz pointed out that it is just an estimate because the government “still has no fully reliable method for tracking those who overstay.”

Whether they cross the fence and walk across the desert or fly in with a visa, the largest portion of illegal immigrants are crossing along Arizona’s southern border. When tougher border security measures were put into place in California and Texas in the mid 1990′s they created a funnel effect into Arizona. The state’s Border Patrol sectors are now the busiest in the country, and the Pew Hispanic Center shows that Maricopa County, which contains the city of Phoenix and its suburbs, more than doubled its Hispanic population between 1990 and 2000. The Hispanic population in Phoenix rose by another 60 percent between 2000 and 2008. This growth stems from illegal immigrants, native-born Hispanics and legal resident Hispanics who have migrated to the state. After this explosive 18-year growth spurt, the greater Phoenix area now has the fifth largest Hispanic population in the United States, behind Los Angeles, Houston, Chicago and Miami. According to Pew, 30 percent of Hispanics in Phoenix are likely illegal immigrants.

For Arizona specifically, the FBI’s Uniform Crime Reporting data shows that crime has fallen in recent years and trended downward over six of the last nine years — all while immigration increased.

Violent crime in particular declined in the state between 2001 and 2004. It rose in 2005 and 2006, then again declined from 2007 to 2009. The latest official statistics of the UCR program show that Arizona’s 2008 violent crime rate is lower than the national average—continuing a trend that has been ongoing since well before the SB 1070 debate. The number of violent crimes in Arizona’s three largest cities, Phoenix, Tucson, and Mesa are also all down.

When Forbes released its April 2009 list of the nation’s most dangerous cities, based on the statistics from the FBI’s Uniform Crime Report of cities with more than 500,000 residents, border towns that would fit in this category such as El Paso, Tex., or San Diego, Calif. were absent. Detroit, Memphis, and Miami were the cities with highest violent crime rates. Phoenix did not make the list.

Despite these numbers, some officials in Arizona, like state Rep. John Kavanagh, R-Fountain Hills, say this does not paint an accurate picture.

“This latest analysis concerning crime in Arizona going down is very misleading. First of all, crime in the overall state is going down. But if you break into metropolitan areas and non-metropolitan areas, we see that crime in our non-metropolitan areas is in fact dramatically increasing 30, 40 percent. I’m talking violent crime now. And I would assume much of that is due to crimes being committed in border towns by illegal immigrants,” said Kavanagh.

But when looking at Arizona’s non-metro statistics from the FBI for 2007 and 2008 (2009’s figures have not been released) violent crimes in these non-metro areas have also gone down. There were 347 fewer violent crimes reported — a 26 percent drop.

Still, Sheriff Paul Babeu, the top lawman in rural/suburban Pinal County, says he is observing criminal activity that may not register in the FBI’s reporting system. He says much of it is related to cross-border smuggling and drug trafficking. He has joined Arizona’s U.S. Sen. John McCain in calling for President Barack Obama to send 3,000 troops to patrol the border.

Babeu said that pursuits of suspected drug traffickers by his deputies are far more common now than in years past.

“[T]hese people are acting crazy, putting people in harms way, including our deputies and our citizens,” Babeu said.

The sheriff’s office turned over one hundred undocumented persons to U.S. Border Patrol between January and May, charging forty-one of them for drug smuggling. Babeu says he supports SB 1070 as another way to combat crime.

“Regardless of what your political opinion is, then it [SB1070] got turned onto on the police officers,” Babeu said. “We didn’t write this law. In fact, I don’t believe it’s the solution, yet I support the law because its uniform enforcement… it gives us another tool.”

A Latino Paradox

In his July 1, 2010, speech at American University, President Barack Obama told the country the current immigration system is broken and laws like those in Arizona have “fanned the flames of an already contentious debate.”

So what is really happening in our American cities? And what kind of role do immigrants really have in the safety of our neighborhoods?

Some researchers actually argue that immigration makes the country safer and that there is a correlation between increases in immigration and decreases in crime.

Highlighting the “Latino Paradox,” Robert Sampson, chairman of Harvard University’s Department of Sociology, notes that there are significantly lower rates of violence among Mexican-Americans, even compared to blacks and whites.

His 2008 study, “Rethinking Crime and Immigration,” argues that neighborhoods with high numbers of immigrants — legal and illegal — are directly associated with lower violence. In fact, immigrant presence was noted as a protection against violence.

After he read a Sampson op-ed piece published in The New York Times, Tim Wadsworth of the Department of Sociology at the University of Colorado at Boulder, wanted to explore this idea that immigration was a missing piece in explaining the crime drop in the 1990s through 2000.

His project, recently published in Social Science Quarterly’s June 2010 issue, is titled: “Is Immigration Responsible for the Crime Drop?” Because of the historical and contemporary importance this question has on criminological theory and public and political debate, Wadsworth wanted his work to provide insight to this complex relationship.

“The thing that often comes up in these debates and these discussions is this idea that immigration is increasing crime. And my study, while not looking specifically looking at Arizona or other border towns, is looking at about 459 cities, virtually all medium to large cities in the United States and suggest that at least in the period between 1990 and 2000, the cities that experienced the greatest increases in immigration tended to be the ones were also experiencing the greatest decreases in crime—and that’s while also considering economic factors, other demographic factors, et cetera,” Wadsworth said in a phone interview.

Wadsworth focused on homicide and robbery in cities larger than 50,000 people. These crime stats are considered most reliable because of the regularity of their reporting. These are the crimes that draw people’s concern and attention. Wadsworth’s findings contradict popularly held notions that high levels of immigration result in more crime.

“When John McCain was talking about this was the worst crime situation he had ever seen, in talking about the border of Arizona, he wasn’t talking about shoplifting. He was at least alluding to the idea that this was serious violence going on. And that especially is just where there is no evidence whatsoever,” said Wadsworth.

This is a very different picture than what is seen and heard regularly in the news and in the rhetoric of many politicians. When asked what kind of reaction he has received because of his work, Wadsworth said the general reaction has varied.

“[The] comments have generally tended to come from people who really don’t believe statistics and they don’t believe the data and they’ve already decided what they think about relationship between immigration and crime and there is very little evidence that is going to convince them otherwise,” Wadsworth said.

But why doesn’t hard data, gathered and analyzed by respected researchers, have more of an impact on the public?

Wadsworth points to two issues: the general misinformed understanding of crime by the average citizen and the feeding frenzy on specific, horrendous cases by the media. Instead of reporting about broad trends or larger context, which Wadsworth says “tend to bore people or put them to sleep,” attention-seeking news outlets often go for the most dramatic story they can find — even if it does not reflect reality.

Wadsworth said he reminds his students that crime rates are half of what they were 20 years ago, telling them they can reassure their parents they are actually safer than their parents were when they were the same age.

Wadsworth’s next project will be replicating this study again once the 2010 Census data are available — to see if the pattern changed during the first decade of the 21st century, a time when crime was not dropping as rapidly and we did not have the boom in immigration that the nation saw between 1990 and 2000.

Moral Panic

Another scholar, Arthur Lurigio from Loyola University in Chicago, agrees that immigration and crime is an issue that is picking up steam.

“It reminds me of a moral panic,” Lurigio said. “Moral panics occur when people believe their values and interests and social order is being threatened and they need to take immediate action.”

He pointed to the Red Scare as another example of when the United States experienced a moral panic.

“When you identify an out-group, they are usually a target for hostility and they are treated monolithically,” Lurigio said. “So, there is one group who we believe is all the same and they are called illegal immigrants and we attribute to them a variety of characteristics, mostly unfavorable, that we believe apply to all of them.”

Lurigio said people in that frame of mind don’t “pay a lot of attention to statistics or other data.”

A contributing factor in the problem of “moral panic” is violence related to the cross-border drug trade, which has grown as Mexico’s president has attempted to crack down.

According to U.S. law enforcement officials, the drug cartels are also diversifying their operations, taking over the business of smuggling humans in the United States — making border crossing in general a more risky activity.

However, Harvard professor Edward Schumacher-Matos argues that drugs and migrants are separate issues that need separate solutions. Schumacher-Matos teaches about immigration policy at Harvard’s Kennedy School of Government. In his work he focuses on the impact of unauthorized immigrants from Latin America on the United States and what kind of options the country should consider when creating immigration policy.

“There is a total conflation of the drug violence issue with the immigration issue, and they are two very different issues and need to be treated separately,” Schumacher-Matos said in an interview. “The overwhelming amount of undocumented immigrants do not commit any crime—other than the crime they committed to come into the country. You know, that is a crime; you’ve got to recognize that.”

Schumacher-Matos said that he recognizes some Americans reject all border-crossers as law-breakers who should be punished but that the larger fear is that they are already violent criminals who will bring more criminal activity to the United States.

“And there is just not a study out there to supports that,” he said. “Not one.”

But he says Arizona does face a major, dramatic crime problem that breeds violence — related to drug trafficking.

“Phoenix today is the drug capital of the United States. It’s replaced what Miami was back in the ’70s and ’80s, if you remember the movie ‘Scarface,’ that sort of thing,” Schumacher-Matos said. He said that crimes like kidnappings are indeed happening, but most often between drug gangs and as a result of safe house raids. Rarely does this touch regular citizens of Arizona.

“It’s really important the public understands,” Schumacher-Matos said. “Most of our political leaders know these numbers. They’re smart people. But they want to play on the perception and build on perceptions and play on fears. And that’s what is criminal if you ask me.”

Schumacher-Matos, as did Wadsworth, pointed out that the 24- hour news cycle makes crime look like it is much more prevalent than it really is, because one event is often repeated many times on the television news, on the radio, and on the Internet throughout the day.

Schumacher-Matos cited the still unsolved March 2010 murder of border rancher Robert Krentz, as an example. Krentz’s murder caused an immediate outcry for more border security and a crackdown on illegal immigrants because unnamed sources said an illegal immigrant might have been involved.

“You don’t make public policy off one murder,” Schumacher-Matos said. “You make public policy based on the facts and trends and what’s really happening.”