Violent death stalks immigrants and others who come into contact with cartels.

TUCSON, Ariz. – Line by line, the police and autopsy reports tell the story of Mario Rivera-Rivera’s undoing along the border.

His head was almost completely wrapped in duct tape. It covered his scalp, eyes, nose, and top lip.

Death on the Border

Explore This Topic:

- Main

- An Execution-style Murder

- Unidentified Dead Common Along the Border

His hands were secured with electrical cord and baling string, then duct-taped behind his back.

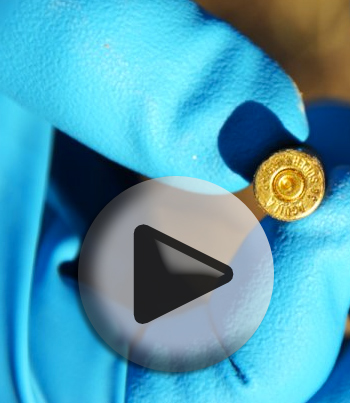

The bullet entered near his right ear and traveled through his skull from back to front.

A pool of blood lay coagulating next to the body — some of it running down an incline in the terrain.

It was an execution.

“There wasn’t any sign of a struggle,” said Detective Martyn Rosalik of the Pima County Sheriff’s Department. “He was walked north of the border and he was either put down on his knees or face down — really hard to tell — and shot behind his right ear.”

The body was found 26 yards inside the United States.

Violence like this is escalating in Pima County, which borders Mexico and is part of the U.S. Border Patrol’s Tucson Sector, by far the agency’s busiest enforcement zone. Much of the violence is attributed to the illicit drug trade — investigators believe this was the case in Rivera’s execution — but some of it is increasingly directed toward illegal immigrants trying to enter the U.S. to work.

Pima County records show that in 2001 there were three violent deaths — a classification that ranges from blunt force trauma to hanging to gunshot wounds — among suspected illegal border crossers. In 2002, the number rose to 14 and has stayed in the double digits ever since. In 2009 there were 24.

“Most gunshot deaths are from drug trafficking — from the rival smugglers,” said Dr. Bruce Parks, the chief medical examiner at the Pima County Medical Examiner’s Office.

The Rev. Delle McCormick, executive director of BorderLinks, an education and activism group that focuses on immigration issues, described drug trafficking and smuggling as “the big business of war on the border.”

That big — and growing — business is taking over illegal immigration and seeking to turn a profit from it. And these businessmen aren’t really interested in keeping their customers safe.

“The smuggling routes are absolutely being controlled by the cartels now,” said Agent David Jimarez, a spokesman for the U.S. Border Patrol in the Tucson Sector. “Because of them, it’s become a much more dangerous place to be.”

That danger extends to Border Patrol agents who deal with everything from being pelted with rocks to armed confrontations with drug smugglers.

In June, in El Paso, a U.S. Border Patrol agent shot and killed a 15-year-old Mexican boy in response to alleged rock throwing.

As cartels have taken over human smuggling routes they have also increased their drug running into Arizona. Last year, 1.2 million pounds of marijuana was seized in the Tucson sector — the most marijuana that’s ever been seized by one sector, according to Jimarez. This year, he said, agents are on track to break that record.

The drug smuggling, the human smuggling and the harsh elements make the Tucson Sector an increasingly dangerous place for illegal immigrants, who can end up as victims even though they took no part in crime, other than paying to be smuggled across. Most of them come to the United States looking for work, and the Border Patrol has stated that the vast majority of illegal immigrants detained and deported aren’t taking part in the drug trade.

There were more than 1,500 deaths in the sector between 2001 and 2009, according to the Pima County Medical Examiner’s Office. Most of the victims succumbed to the harsh elements. The causes of more than 500 of these deaths are still undetermined, mostly because the bodies were so badly decomposed by the time they were found that bones were all that remained.

But of the deaths for which autopsies have determined causes, about 17 percent of them were violent in nature. And for all but a few of them, it’s likely the killers will never be identified.

Murders in the desert are among the toughest to solve because Mexican authorities aren’t always willing to cooperate with their counterparts in the United States, Rosalik, the Pima County Sheriff’s Department investigator said.

Such is the case with Mario Rivera-Rivera, the victim who was tied up and shot in the head. His body was found Nov. 2, 2009, and despite intensive investigation there have been no arrests.

Rosalik said Rivera’s family broke off communication with the sheriff’s department after they identified the body and he does not know if they reported the case to Mexican police — leaving the investigation on the American side at a dead end.

“The thing that’s really frustrating in a case like this is that we can’t go into Mexico,” Rosalik said.

There are some clues as to what might have happened. Authorities believe Rivera was not trying to enter the United States but likely was forcibly taken north across the border to die, perhaps to throw off investigators.

Rivera was a horse breeder outside of Sonoita, Sonora a city of about 10,000 located across the border from Lukeville, Ariz. On Oct. 31, 2009, Rivera walked with his dog away from his farm and wasn’t seen again until he turned up dead just 26 yards inside the United States.

His family knew something was wrong when his dog returned to the farm alone an hour and a half after Rivera first left. And there were other clues that led family members to believe something sinister had happened.

“His baseball cap was laying on the ground and that was unusual because he never took his baseball cap off,” a family member said in the police report.

Two days later, Agent J. Lewis of the Border Patrol was the first to stumble upon Rivera’s body.

On patrol around 9:30 a.m., Lewis saw a water bottle cap and footprints crossing from the Mexico side of the border into the United States. He followed the tracks north.

In his report to sheriff’s investigators Lewis said he found a Hispanic male lying on his stomach surrounded by foliage. The victim was dressed in brown boots, white pants, a green belt and a sweatshirt. Lewis notice that the victim’s head was wrapped in duct tape and that his hands were tied behind his back.

Another interesting detail: a horse bridle was tied to the body.

Rumors going around Rivera’s hometown of Sonoita said the drug cartels murdered the horse breeder. Family members told authorities they believe Rivera could have been doing something illegal and that they too believe his murder has ties to the cartels.

The horse farm Rivera owned is close to the border in an area known for marijuana smuggling and as a launching point for those trying to enter the United States.

According to the police report, Rivera had sold horses to local drug dealers to be used for drug smuggling into the United States. And, according to the police report, people in Sonoita said that Rivera had lost a drug load that he was storing at his farm.

Rivera was found 14 miles west of the Lukeville, Ariz. port of entry — in the Organ Pipe Cactus National Monument, where violence and drug smuggling is nothing new.

The National Monument land shares a 31-mile border with Mexico. In recent years Park Rangers have been drawn into drug trafficking cases, arresting smugglers and seizing loads. In 2002, U.S. Park Ranger Kris Eggle was killed by a suspected drug cartel hitman fleeing Mexican authorities.

The escalating violence is not lost on many who are smuggled into the U.S. illegally. Dozens of recently interviewed border crossers attest to the growing danger.

One, Juan, has tried his luck in the desert twice — and was recently waiting to go for a third time. He had lived in North Carolina with his family for 15 years before being deported for driving without a license.

On the day he spoke to a reporter, Juan was at the Kino Border Initiative, a shelter for deportees and potential border crossers in Nogales, Mexico. Juan washed dishes, ate, and talked to other deportees while waiting for the right opportunity to return to his wife and children in North Carolina.

Juan knows from experience the danger that awaits border crossers in the desert, and he knows he is lucky to have twice survived the trip.

“Some groups, they get jumped by guys. They take their money, clothing, and they abuse the women – they get violated, you know,” he said.

Juan’s first journey to the United States, he says, was uneventful. It was in 1995 and he was in search of a better life. His brother said, “Don’t worry about a visa, you’ll be fine without it.”

And Juan was fine for a few years. After being deported for the first time in 2002, he ventured into the desert to cross again.

He crossed successfully but he could tell the border was now a more violent place. He believes it was worse because of 9/11. Ramped up security on the border, Juan thinks, has caused a more ruthless and violent environment for crossers to navigate. The number of Border Patrol agents has increased from 6,000 in 1996 to 20,000 and so the risk of being caught has risen dramatically. So have the prices coyotes charge to smuggle people.

Last year, 241,000 people were apprehended in the Tucson Sector. According to Jimarez, an estimated 20 percent of those people had criminal backgrounds, ranging from theft to murder. The other 80 percent are the people who may get caught in the crossfire.

Juan doesn’t want to cross again but he probably will. What he wants is to bring his family back to Mexico. “It’s not such a good idea to cross the border,” he says in wry understatement.